The Basics - Getting Started August 6, 2001

The Basics - Compositing in FCP

A basic guide to building a 'virtual set'

By Phil Ashby

First steps towards your Award

When the scenery you see in the background of a shot has been added in post-production, and especially when it's been computer generated, that's a 'virtual set'. Putting the elements of the shot together is as much an editing art as a science, just like audio mixing, shot juxtaposition, and all the other wonderful effort-intensive skills you can now spend time on. This particular art is called 'compositing'.

A few words in justification: the sort of compositing this article describes isn't going to win any Academy Awards for special effects but has got two things going for it:

1) it's the sort of bread-and-butter process that us ordinary folk need to get on with our daily tasks of editing, and2) the techniques you'll learn may come in useful for that Award one day.

Compositing is the term we use whenever more than one video track comes into play in a shot - at its simplest, when text is superimposed, or when a picture-in-picture effect is utilised. I'd guess the next most common use is to add a different background to a shot. You've got a presenter against blue-screen or (as we'll see here) a plain black backing, and you want to change that backing to something else - a video shot or a still, say.

What we're aiming for

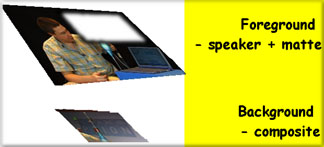

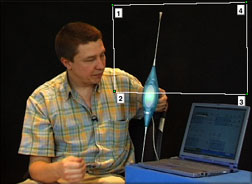

Figure 1a shows the master (foreground) shot: a presenter with the thing he's going to talk about. (Should you wonder, it's a digital radio gizmo that attaches to a pc). The original intention was to shoot the piece in the lab or at an office desk, but we had to change plans, and record this (and several other pieces) against a black drape. Figure 1b shows the end result we're aiming for.

Figure 1a. Master Shot

Figure 1b. Completed Composite

You may be wondering why we didn't make shoot against the familiar blue or green screens for compositing. (Known as Chroma Key or, in more traditional corners of the TV world, colour separation overlay, CSO). FCP can do chroma keying, but it wasn't feasible on this shoot, because of lighting, time and clothing constraints. By which I mean, another guy came wearing blue.The first rule in succesful, that is, well keyed, compositing, is to get the best original material at the shoot. Lighting is more critical for colour keying than against a black cloth. Apart from good portaiture of the presenter, it's essential to get an even light onto the screen, with as little shadow from the artist as possible, and a good rim or back light on the presenter, to avoid too flat a 2d look to the end result.

A safer option is to shoot against black. In the simplest case, it's just a matter of leaving room in the framing of the master shot to allow for a PIP. No other keying is involved, but the simple PIP wouldn't work in the example of figure 1, because of the antenna and hand that are in shot. The presenter and props need to be in foreground, the fill-in as background, and a simple PIP won't do that - the inserted picture will obliterate the antenna.

Building up to the result

Figure 2 shows a schematic form of a composite layout that I've used often. The general rule in FCP compositing is that the topmost video track is what you see, except where it has areas of transparency ( or, in FCP terminology, 0% opacity). So I'm going to cut a rectangular hole in the top picture, through which it'll be possible to see the background graphic, with the aerial laid on top of (that is, in front of) it. So this background is itself a composite, of a) the presenter/aerial shot, and b) the screen shot with the product name on it. It's by no means the only method of getting the end composite - but it works most often when I need something good in a hurry.

Figure 2. Schematic form of a composite

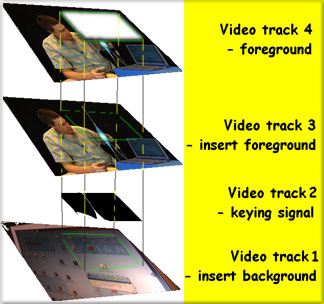

Figure 3 shows the fuller schematic. I've expanded the middle picture into the three layers that FCP uses to produce it. You can see that track 2 is a black and white signal. It's going to act as a control over the two tracks (1 and 3) that lie above and below it: the black areas select one track for display, the white areas select the other track. All three of them make up, as I've said, a 'composite' and track 2 acts as a key (or matte - the terms are pretty well interchangable). It's generated using the luma key filter (this term is explained later on). Remember this is a movie, there are 25 (30 in NTSC) frames a second. We could draw the keying signal as a black and white graphic (using, for instance, Commotion DV) but at 25 frames a second this can take a lot of time. It's preferable to have the image (that is, the presenter who's in track 4) generate its own matte where possible, and that's what we'll do here. Key extraction is the most delicate and crucial part of this process, and is almost certainly where you will spend most time when adjusting composites.

Figure 3. Fuller schematic

What we want is called a 'luma key'- extracting the key signal from the luminance (brightness) of the image. That's why shooting against black is helpful - essential actually. We'll need to treat the image in an extreme way to reach a black/white frame that will key (or switch) cleanly. You may well find that there's a good enough contrast between the black of the drape and the rest of the picture to be able to use the whole frame as a luma key - just relying on the black of the drape within the entire picture to do the keying. The problem with luma keying is that there are often areas within the picture (not the drape) whose brightness level lies too close to the keying level, and you can spend a long long time adjusting them out, or removing them with other matte levels. That's why I've confined the keyed area on this material.On the timeline

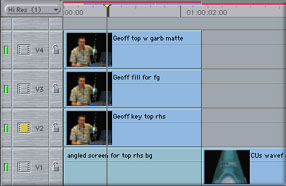

Figure 4 shows the FCP timeline for this composite. The video tracks match the layers of figure 2. The vital detail is that tracks 2 to 4 contain precisely the same picture material, and that you don't nudge any of them out of sync. Before I got this far, I'll have finalised the main picture and sound cut, working with just one video track: I'll always save a duplicate of the sequence at that point, as a safety reference.

Figure 4. FCP timeline

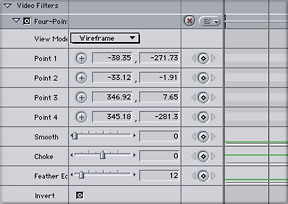

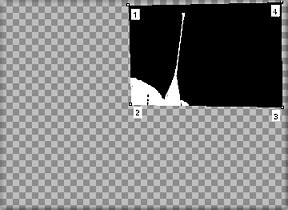

So, with the main cut for content agreed, I'll shift the presenter video clips to track 2. (Dragging with the shift key depressed stops material moving any direction but upwards). Then I edit the background shot into track 1.Before I generate the other tracks, I make the 'cutout' on the presenter shot. That's done with a 'garbage matte'. That's a video filter, dragged onto the viewer. I've used the 4-point garbage matte - what it does is create a hole in the picture, through which the lower video layers will be visible. Adjusting the position of these mattes takes a bit of getting used to in FCP. You need to position the playhead over the shot in the timeline, so the CANVAS will give you a feed of the composite result. Then highlight the clip on the top track.

The garbage matte filter has four position controls (accessible in the Viewer, under the Filter Controls tab). With View Mode in 'Wireframe', click on the cross-hairs to set the positions for points 1 through 4 in turn and adjust to give the right size and position of matte (don't worry about the missing hand at this stage).

Figure 5 shows you the clip in the viewer, Figure 6 shows you the filter controls I've used to generate this picture. Note the check in the 'invert' box: it's vital you get this the right way round to select which part of the image you lose. You'll see the three adjustments for 'smooth', 'choke' and 'feather edge' - adjust these to taste to get the best blend when you've finished the compositing. Make sure that you leave the 'View Mode' set to Final when you've finished, or your timeline preview won't show the composite.

Figure 5. clip in the viewer

Figure 6. Filter controls

I now copy and paste this clip into two tracks above. Select the clip by clicking on it. Apple C (to copy), then target the new video track, and Apple V (to paste). Alternatively, Shift + Option (Alt) and drag will place a copy of a clip rather than moving it - but I find this doesn't always work (I think I lack the co-ordination rather than the Mac). I do the copy and paste AFTER I've put the garbage matte on, to give a guide as to which area of the clip I am working on, when setting key levels. As you can see from the diagram, I've renamed the clips (control click on the clip, select 'properties' and type into the title box) to make it obvious what each one is for - if you do nothing, they'll all have the same name which can get confusing should you re-visit the project after a while. (I only rename the first clips in the timeline though)Building the composite background

Now we need to set up the composite of tracks 1 to 3. Select the clip on track 3 and Modify>Composite Mode>Travel matte - luma. This composite means that FCP will use the material in the next track down - so it's video track 2 here - as a key: I think of it as a sandwich, with the key signal the filling in the middle.

Select the clip in track 2 and apply the 'luma key' filter. You use this filter to generate an extreme black and white version of the clip, which is your key. First off, get a rough adjustment by dragging the video tab in the viewer out to the right: you now have access to the filter controls, at the same time as seeing the result.

Figure 7 shows the picture, Figure 8 the filter controls I used to get it. I've chosen View Final, Key Out Darker, and Copy to RGB (explained below). Finding the right combination of Threshold and Tolerance is usually a delicate operation - and it's why I suggested keeping the garbage filter in, so that you concentrate your efforts on the area you need to. You will also need to uncheck the 'invert' box on the garbage mattes in tracks 2 and 3, so that the opposite areas of the frame are matted out, compared to track 4.

Figure 7. Shows the picture

Figure 8. Filter controls

An aside on Alpha channelsOne of the dropdowns in the filter controls sets the extracted key to 'RGB'or 'Alpha'. In this context, it's just a matter of choice of routing - we'll use RGB (here, it means the same as luma) to match the choice we made when we set the travel matte on Track 3. You can think of the 'alpha'channel as a fourth signal in a picture, with RGB. Alpha sets the transparency of the shot. The good news is that you can save the alpha channel on stills or uncompressed quicktime (that is, using the 'animation'codec - saving with millions of colours, +, the + being the alpha channel). What you can't do is save alpha in a DV compressed video, there being no bandwidth to spare!

Final Adjustments

Once you've got a halfway decent key on Track 2, drag the viewer video tab back to the viewer window, and have a look at the final composite in the Canvas window. Make sure the playhead is positioned over the correct part of the timeline.

By now you'll have noticed the render bar - step through a second at a time to check the keying through the length of the clip - note that the luma key filter controls CAN be keyframed. But you shouldn't really need to do this unless there's been a big change in the lighting.

The final adjustment is to soften the edges of the matte in layer 4 to blend in (to taste). Then you can delete the garbage filter from tracks 2 and 3 to save unnecessary rendering time. As I said, it's useful in preview, but is not needed in the end result - the top level garbage filter has set the areas up. I'm not too sure, by the way, whether this does speed up the final render - it's one filter fewer for FCP to work through, but FCP has to do more work creating the luma key: I suspect this is a content-dependant step.

If, as is more than likely, you have a sequence with several similar setups, there's an important shortcut when it comes to applying filters and mattes. For each video track, firstly select the clip you have adjusted, and Apple C to copy it. Then select the other clips you want to treat and Alt (Option) V. This really useful key combination pastes filters (and any other clip 'attributes'such as motion, repositioning) from the selected clip. Do this for each track separately. You then need to check each of the composite shots for keying, to see if you need to adjust anything for different content or lighting, but most of the time only minor adjustments should be needed.

Render and read on

By now, it's time to hit 'render'and while you're waiting, read a resume of the effects we've used and the general principles:

FCP looks on video tracks from the top downwards: so the topmost layer is the foreground visual.Usually the upper layer controls the visibility of layers underneath, EXCEPT when a travel matte is applied. When it is, the matte layer switches between the layers above and below it, in a 'sandwich' mode.

The garbage matte is used to create an area of transparency in a clip, through which lower tracks can be seen The luma key matte treats a clip to produce an extreme keying signal.

I've only scratched the surface of the effects, filters and compositing methods that FCP offers, and as I said, this method is by no means the only way to get to the desired effect. Although it may seem I've been rather generous in using so many layers, I've found with experience that having the key in a clearly separate video track saves a great deal of time and trouble when re-adjusting a week later.

Phil Ashby is producer / editor for production company Bright Filament, who specialise in science/technology and education based programmes in all electronic formats known to man and woman. His biggest fears for the future are that one day Apple will perfect FCP and there will be no problems left to solve, the accumulated weight of manuals will overstress the structure of his house and that render times will shrink to negative numbers, thus increasing the working day.

copyright © Phil Ashby 2001All screen captures, images, and textual references are the property and trademark of their creators/owners/publishers.