Book Review - Digital Video

February 4, 2002

Nonlinear/4

A Field Guide to Digital video and film editing

Triad Publishing Company

Book Review - Digital Video

February 4, 2002

Nonlinear/4

A Field Guide to Digital video and film editing

Triad Publishing Company

ISBN 0-937404-85-3

Like many new editors, I came to Final Cut Pro with no NLE experience nor any knowledge of video whatsoever. In fact when I started, just over two years ago, there was not a single book on FCP. Since that time there have been a number of excellent books published about FCP. I have bought and read all of them.

During the past two years I have learned the terminology used with FCP video. But my knowledge is FCP-centeric. I have little understanding of video, it's relationship to film or it's history.

Last week I discover a book "Nonlinear/4 written by Michael Rubin. I can best describe this book as a complete reference guide to all things video. But its actually more.

The book starts off with a 'Fundamentals' section that consists of an introduction to Film and the history of Video. We are then moved into the early days of video and linear video editing and then into the digital era and nonlinear editing. What we learn from this section is the methods that were developed to make film and video work together. Telecine and 3:2 pull down, frame rates and transfer, drop frame and non drop frame, Time Code, EDLs, audio and more.

Rubin covers much more in this book, including the role of computers and their requirements that came into play in nonlimear editing. Digital storage, Hard Drives, RAIDs, Bandwidth, Compression and Codecs, computer and video pixels, type, aspect ratios, color space, light and fundamentals of video color, chrominance and luminance, Component and Composite video, resolution, HDTV and it doesn't stop there.

The book moves on into the world of editing and then distribution including everything from Broadcast, Film, High Def, Digital television, QuickTime, the Web and DVDs.

If I have made it sound like this book is a meandering tour through the past, it's not. Each element covered in this book is in it's own section. Each section is brief, concise and clearly written. Very simple (read clever) analogies are employed to help the reader gain understanding. While there is technical information, the book is not overly technical. There is a great deal of art, illustrations and photos. This art furthers the learning experience and is one reason that the book works so well, the art really illustrates the lessons being taught.

I have mentioned that the history of film and video runs throughout the book. This history is essential to understanding how and why video is what it is today.

I learned a great deal from this book and now have a better understanding of why things are the way they are. Our modern day NLE Digital video is the result of a long legacy, going all the way back to the early days of film. This book is a great reference guide as well with a full index at the back.

I am really glad that I came across Nonlinear/4. I truly have a better understanding of what's going on with Video and how it works. This knowledge will certainly help me with FCP. I have included one excerpt from Nonlinear/4 below as a sample of the way that the book works.

Enjoy,

--ken

Book Excerpt from Nonlinear/4

"ASPECT RATIO BASICS"

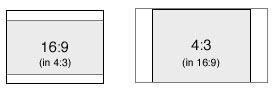

The shape of a frame, whether film or video - analog or digital - is traditionally described by the ratio of its width to its height. This ratio is called the aspect ratio. Television (whether NTSC or PAL) is 4:3, which means it is four units wide by three high. Therefore, if an image is 10 inches long, the height would be 7.5 inches; if it is 640 pixels long, it would be 480 pixels high. Another way of writing this ratio is 1.33:1.

Traditional film as projected on a big screen typically has an aspect ratio of about 16:9 (actually 1.85:1). This is far more "horizontal" than television. Some say film was originally presented in this wide format because it was more like the proscenium of a stage, as you would see it from the audience during an opera, for instance. Regardless, the issue of aspect ratio becomes important when one wants to play a movie on TV, but it's the wrong shape. It's also an issue when a director shoots DV, for example, and hopes to transfer it to film. Or when producing a TV show to be seen by audiences in both NTSC and HDTV. Aspect ratio is a hot topic when the subject of a digital, universal master format is discussed.

Here are the two principal aspect ratios for moving pictures. The darker, more "vertical" rectangle is 4:3; the grey horizontal rectangle is 16:9 (below).

List price: $39.95 U.S.

413 pages

Review By Ken Stone

By Michael Rubin

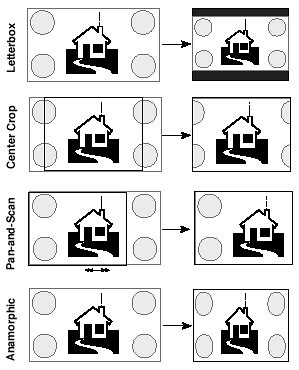

If you put a 16:9 image on a 4:3 display, it will only fit if you shrink it down about 25% and leave blanks along the top and bottom of the screen. Similarly, a 4:3 image will only fit on a 16:9 display if you shrink it down and leave blank spaces along the sides. Thus, there are compromises that must be made in order to convert material from one format to another (below).

Methods

Shrinking the image down and leaving bars at the top and bottom of the screen is called letterbox format; it's the most common way to transfer film to tape, without having to modify the image per se.

But if you decide to avoid the bars and simply crop the image, and ignore any aesthetic considerations, you might perform a center crop-which can be remarkably unsatisfying because it chops off characters and action not in the middle of the screen.

In practice, the most common technique, performed in telecine and nonlinear online sessions by Hollywood studio clients, is called pan-and-scan. In this case, the operator moves the 4:3 frame around on the 16:9 image, keeping the most important material in-frame at any given moment.

But if you decide to avoid the bars and simply crop the image, and ignore any aesthetic considerations, you might perform a center crop-which can be remarkably unsatisfying because it chops off characters and action not in the middle of the screen.

In practice, the most common technique, performed in telecine and nonlinear online sessions by Hollywood studio clients, is called pan-and-scan. In this case, the operator moves the 4:3 frame around on the 16:9 image, keeping the most important material in-frame at any given moment.

Finally, you could convert shapes by using an anamorphic compression (meaning that the image is squished along one axis but not the other). But people tend to dislike having their images squished. Research has shown that a squish of 5% is undetectable, and 7% is detectable, though not objectionable. But these manipulations are a far cry from the 25% squish or stretch needed to convert these aspect ratios fully.

For the most part, going the other way (changing a 4:3 image to 16:9) involves variations on these conversion methods - called pillarbox, middle cut, and tilt - and - scan.

With frame conversions in both directions, newer technology makes it possible to mix methods. For example, a little letterbox plus a little center crop, plus a tiny bit of anamorphic squeezing can all be used together as a compromise, better approximating the original source. These blends, as they are called, reduce the necessity of having to make aesthetic judgments for each individual scene. All methods will continue to be needed as long as 4:3 and 16:9 coexist, in their uneasy truce, in the name of convergence.

Michael Rubin began his career at Lucasfilm, where he was instrumental in the development of training for the EditDroid, and in introducing the Hollywood market to nonlinear editing for film. He spearheaded the nonlinear post-production of (1989) Lonesome Dove; He assisted Academy Award-winning editor Gabriella Cristiani with Bernardo Bertolucci's The Sheltering Sky (1990). In 1991 he was also editor of one of the first television programs to be edited on the Avid. He is the author of Nonlinear: A Field Guide to Digital Video and Film Editing is now in its fourth edition; and recently released his first book for consumers--The Little Digital Video Book (2002). His seminar "Introduction to DV" -- coproduced by the American Film Institute and Columbia University, is available online at www.fathom.com. Visit Michael Rubin's web site.

Nonlinear/4

copyright © 2001 by Michael Rubin

All Rights Reserved. This material is excerpted from NONLINEAR/4 and is used with permission.

You can purchase 'Nonlinear/4' from the lafcpug store.

Review copyright © www.kenstone.net 2002