October 29, 2007

and when to convert to something else.

There is some confusion, and probably more than a little difference of opinion, in when to stay in the native codec of the source, and when to convert to some other codec for editing and output. There's a good reason for the confusion, because there isn't one simple answer. In this article I plan on providing some reasonable guidelines, specific examples and what the exceptions might be.

Some basic rules of thumb

- Generally speaking you want to do as few conversions as possible. Every conversion involves some loss of quality even when the loss is small and you're going up to a theoretically higher quality format.

- Only convert to a higher quality format. (This won't improve the quality of your material, but it will minimize your losses.)

- If you're going to output in the same format that you shot, then you would almost always stay in the native format throughout. This would particularly apply to DV/DVPRO/DVCAM, DVCPRO 50, and DVCPRO HD, where the edit output is frequently in the original source format.

- If you're going to output into a format other than the one you shot with, convert to that format as quickly as you can, usually during capture or digitize. Definitely you want to get to that format as quickly as you can even if you can't convert on capture.

Now I've given you four nice simple rules, I'm going to spend the rest of the article complicating matters because that's the kind of guy I am. I mean, in order to help you understand why these are good rules-of-thumb and how and when you should break them!

It is true that every conversion from one format to another causes some quality loss in the picture, even when going from a nominally lower, to nominally higher, quality. In practice you can safely ignore this loss because it's usually not visible, but take on board that format changes should be avoided unless there's a good reason.

So, let's consider input formats and take a look at the advantages and disadvantages of native and non-native workflows. But, before we get to that, what about formats that have no native equivalent in Final Cut Pro?

When you can't stay native

Final Cut Pro supports a lot of native codecs, but some acquisition codecs aren't supported natively in Final Cut Pro, like when your source is HDCAM or HDCAM SR, in HD or Digital Betacam or IMX in SD. Despite what you may have been led to believe, all acquisition codecs are compressed - Sony uses the euphemism "bit rate reduction" - but that, my friends, is just marketing-speak for compression. Even HDCAM SR (the peak of quality for field acquisition) has mild (and near lossless) compression.

Final Cut Pro supports a lot of native codecs, but some acquisition codecs aren't supported natively in Final Cut Pro, like when your source is HDCAM or HDCAM SR, in HD or Digital Betacam or IMX in SD. Despite what you may have been led to believe, all acquisition codecs are compressed - Sony uses the euphemism "bit rate reduction" - but that, my friends, is just marketing-speak for compression. Even HDCAM SR (the peak of quality for field acquisition) has mild (and near lossless) compression.

Don't be afraid of compression, it doesn't always mean you lose quality as any viewer of HDCAM SR will testify. A .sit or .zip file is compressed but you always get out the other end what you put in, exactly! If it didn't work that way, applications wouldn't run and pictures would look all messed up.

Don't be afraid of compression, it doesn't always mean you lose quality as any viewer of HDCAM SR will testify. A .sit or .zip file is compressed but you always get out the other end what you put in, exactly! If it didn't work that way, applications wouldn't run and pictures would look all messed up.

For sources where there is no native codec available what to use? Well, before Final Cut Studio 2 the answer was simple: DVCPRO 50 - unless the delivery requirements specified full 486 raster. DVCPRO 50 is, like DV, 480 pixels high. The difference is all hidden in Action Safe and never visible on a TV, but some companies require full raster, meaning those older systems have to spec out for the much higher data throughput and storage requirements for uncompressed editing.

Now we have ProRes 422 and that is both full raster and so close to lossless as to not matter, and more importantly, to never be detected by any QC engineer.

In HD, coming from HDCAM or HDCAM SR, you would most certainly use ProRes 422 during editing. Only the most particular would bother going to uncompressed HD for the conform because there would be no visible or technically measurable advantage to going uncompressed. (Oh heck, I'm going to get email about that, but I stand by it.)

Verdict: Capture to ProRes 422* or uncompressed if your delivery requirements specify uncompressed editing in which case you'd use ProRes 422 during offline, conforming to uncompressed at the final stage.

What is ProRes 422?

As I said above, ProRes 422 is both full raster and close to lossless. In other words it's a magic codec from the powerful wizards in Cupertino. Maybe not, but it is one of a new generation of codecs that use the increased CPU and GPU power in modern computers to gain seriously increased encoding efficiencies. I think they use digital elephants to squash down the data rate!

As I said above, ProRes 422 is both full raster and close to lossless. In other words it's a magic codec from the powerful wizards in Cupertino. Maybe not, but it is one of a new generation of codecs that use the increased CPU and GPU power in modern computers to gain seriously increased encoding efficiencies. I think they use digital elephants to squash down the data rate!

ProRes 422 gives us true quality at modest data rates (140 and 220 Mbits/sec) using the full raster of the image and an all-I frame structure. As we'll see shortly, many codecs "compress" by storing fewer pixels than full raster would require. For 1080 HD, ProRes 422 uses 1920 x 1080, which is the full raster. HDCAM, for example uses only 1440 x 1080 pixels and DVCPRO HD uses only 1280 x 1080 pixels. Both these formats stretch out to full 1920 x 1080 for playback.

Because it's all I frames, i.e. every frame is complete within itself, it takes less processor power to play back and to render, speeding your workflow.

Apple's ProRes 422 is very comparable to Avid's DNxHD codecs, and if you think it's a miracle getting the 1.5 Gbit/sec bandwidth of uncompressed HD into 140 Mbits/sec, check out Avid's 36 Mbit/sec "offline" HD codec.

HDV Source

Let's get this one out of the way first because it's surely the most controversial. HDV (like XDCAM) is a long GOP MPEG-2 codec. It has a single keyframe (I frame in MPEG-2 speak) followed by) 14 other frames (in 60 Hz countries like the USA) to make up a 15 frame Group Of Pictures. (No Elephants associated with this GOP.) The frames in-between are calculated by looking at blocks of pictures and figuring out where those blocks move between the frames, then processing those blocks and the information about how they move. Some of the information is presented as (P)redictive forward frames, and some as (B)ackward prediction. Together they make up the IPB structure of an HDV datastream. (20,000 MPEG engineers were just horrified with the world's least technical explanation of Long GOP MPEG-2 ever, but it's close enough for our purpose.)

Let's get this one out of the way first because it's surely the most controversial. HDV (like XDCAM) is a long GOP MPEG-2 codec. It has a single keyframe (I frame in MPEG-2 speak) followed by) 14 other frames (in 60 Hz countries like the USA) to make up a 15 frame Group Of Pictures. (No Elephants associated with this GOP.) The frames in-between are calculated by looking at blocks of pictures and figuring out where those blocks move between the frames, then processing those blocks and the information about how they move. Some of the information is presented as (P)redictive forward frames, and some as (B)ackward prediction. Together they make up the IPB structure of an HDV datastream. (20,000 MPEG engineers were just horrified with the world's least technical explanation of Long GOP MPEG-2 ever, but it's close enough for our purpose.)

Not surprisingly, calculating any given frame in the Group is processor and memory intensive as all frames in the GOP have to be used to calculate any given frame. That said, Apple did a pretty good job with HDV support and I've done a lot of HDV editing natively both with a PowerBook G4 1.5 GHz (up to 3 layers at a time off a G-RAID) and with a Quad G5. The editing experience is not that much different than with DV.

So, if you're starting with HDV and not going back to HDV tape, and don't plan on a lot of heavy compositing or color correction, then staying in HDV natively isn't that big a deal. It's when you go back to tape that HDV hits you with a long (and we mean long) conform, where it rebuilds the GOP around each of your edits. Ouch.

So, conventional wisdom has always been to "get out of HDV as quickly as you can". Great advice and consistent with rule 4 above: get into your output format as quickly as you can. So, unless you're staying in HDV and not going to tape (say DVD, Web or HD DVD) then you probably want to convert to ProRes 422. Before ProRes 422 there wasn't a great choice to convert to, unless you wanted to go to the expense of uncompressed HD.

Why Not DVCPRO HD?

Yes, you down the back, what do want? Why not use DVCPRO HD? Nice that you've been paying attention! DVCPRO HD is a less-than-ideal choice for converting from HDV (or any other source) for two reasons. Sure, it's 4:2:2 and it's all I-frames, so it's easier on the CPU, but DVCPRO HD has less luminance resolution (the resolution that counts for sharpness) than HDV. Hard to believe but at "720" HDV is full raster 1280 x 720 but DVCRPO HD is 960 x 720. Darn.

At "1080" HDV is, like most formats, 1440 x 1080, while DVCPRO HD is 1280 x 720 (although it will also support 1440 x 1080 if capturing through an AJA or Blackmagic Design card). Losing real resolution is never a good idea - see rule 2 above.

The other reason that makes DVCPRO HD a less-than-perfect choice to convert to, is that it's a completely different compression scheme than HDV. So you end up with the lesser of both! Ooops. (Bonus point: the technical name for this phenomenon is "concatenation", always useful to throw around at parties. Well, it's a hit at the geek parties I go to, anyway.)

Like I said, ProRes 422 is full raster at both 720 and 1080 resolutions, all I-frame, and virtually lossless compression, so it's a good match for HDV if you don't want to stay native. The 140 Mbit of ProRes 422 version is the best match for 8 bit HDV. While it's just over 5x the data rate of HDV native (25 or 19 Mbits/sec), it's still within the capabilities of FW 800 and eSATA drives, without needing a RAID.

Verdict: Stay native when outputting to HDV, DVD, HD DVD or to the web, otherwise convert to ProRes 422 after initial capture (via FireWire), or convert during.

Converting to ProRes 422

Converting to ProRes 422 from HDV can go two ways: spend money on hardware or spend time on software conversions. (Haven't we heard that before!) In a perfect world you'd play out of Sony's new HVR 1500 to HD-SDI which would be captured with a card/box/adapter from Blackmagic Design or AJA. AJA's new Io HD is a perfect choice because it has the ProRes 422 codecs in hardware. That means the computer can be a little less powerful, making the Io HD workable with a MacBook Pro Quad G5.

Converting to ProRes 422 from HDV can go two ways: spend money on hardware or spend time on software conversions. (Haven't we heard that before!) In a perfect world you'd play out of Sony's new HVR 1500 to HD-SDI which would be captured with a card/box/adapter from Blackmagic Design or AJA. AJA's new Io HD is a perfect choice because it has the ProRes 422 codecs in hardware. That means the computer can be a little less powerful, making the Io HD workable with a MacBook Pro Quad G5.

Without an Io HD we could use any Decklink or Kona card, or Blackmagic's Multibridge series to bring in the HD-SDI and compress it during capture to ProRes 422 using the computer's own resources. This is the same as coming in HD-SDI and compressing to any other codec, except ProRes 422 (like all big elephants) is a hungry beast and you'll be needing a MacPro for consistent real-time compression from HD-SDI to ProRes 422.

Coming in HD-SDI and compressing to ProRes 422 works from any HD source that can provide an HD-SDI output. Pick the right deck and any format can be provided as HD-SDI. We can also use SDI for Standard Definition signals, which ProRes 422 can reduce down proportionally.

You don't have the coin for a MacPro and capture card, or an Io HD? I guess you're just plain out of luck if you want real time conversion. Or even quick conversion. If you want to work with ProRes 422 and you capture HDV, DV or XDCAM HD over FireWire then the first step is to capture native: the file copy from HDV tape to HDV QuickTime files (or DV on tape to DV QuickTime files and so on).

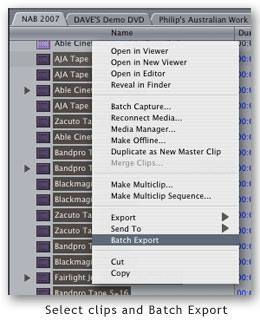

Once captured onto disk, do a Batch Export of your captured clips to the appropriate ProRes 422 codec, or use Media Manager to convert. Check out the end of the article for detailed instructions.

XDCAM HD

XDCAM HD is really just grown-up HDV. It has three data rates: 19 Mbits/sec, 25 Mbit/sec and 35 Mbits/sec. Since it's more compressed than HDV it's no surprise that few people choose the 19 Mbit/sec setting. At 25 Mbit/sec XDCAM HD is identical to HDV (with a better camera at the front, for sure) so it's the 35 Mbit/sec version that's appealing. At 35 Mbit/sec Variable Bitrate (VBR) the quality is a big step up on HDV but is still long GOP MPEG-2. Like HDV you can edit natively in long GOP MPEG-2; convert to ProRes 422 or capture via HD SDI and work uncompressed. Unless your delivery specifications specify editing uncompressed, use the Log and Transfer window to capture or convert to ProRes 422 or follow the directions above and convert in real time. You can then output to the finishing format you need for delivery. (XDCAM HD, like HDV is not a good choice for mastering format.)

XDCAM HD is really just grown-up HDV. It has three data rates: 19 Mbits/sec, 25 Mbit/sec and 35 Mbits/sec. Since it's more compressed than HDV it's no surprise that few people choose the 19 Mbit/sec setting. At 25 Mbit/sec XDCAM HD is identical to HDV (with a better camera at the front, for sure) so it's the 35 Mbit/sec version that's appealing. At 35 Mbit/sec Variable Bitrate (VBR) the quality is a big step up on HDV but is still long GOP MPEG-2. Like HDV you can edit natively in long GOP MPEG-2; convert to ProRes 422 or capture via HD SDI and work uncompressed. Unless your delivery specifications specify editing uncompressed, use the Log and Transfer window to capture or convert to ProRes 422 or follow the directions above and convert in real time. You can then output to the finishing format you need for delivery. (XDCAM HD, like HDV is not a good choice for mastering format.)

Verdict: ProRes 422 all the way via Log and Transfer; uncompressed only if you really have to.

DVCPRO HD

With DVCPRO HD of all flavors you'll stay native almost all the time. Native support in Final Cut Pro is excellent; it's a 4:2:2 codec with moderate compression that stands up well to color correction and compositing. There is little reason to convert to something else as DVCPRO HD is a reasonable master-tape format as well, and can be easily dubbed to HDCAM or D5 for delivery. There is little point working with uncompressed as you can't get better than what you start with.

With DVCPRO HD of all flavors you'll stay native almost all the time. Native support in Final Cut Pro is excellent; it's a 4:2:2 codec with moderate compression that stands up well to color correction and compositing. There is little reason to convert to something else as DVCPRO HD is a reasonable master-tape format as well, and can be easily dubbed to HDCAM or D5 for delivery. There is little point working with uncompressed as you can't get better than what you start with.

Verdict: Native all the way.

DVCPRO 50

There absolutely no reason to deviate from native when working with DVCPRO 50, unless your delivery requirements absolutely insisted on 720 x 486 output (and even then I'd consider blowing up the DVCPRO 50 master 1.25% at a post house - no-one will ever know.) There is little advantage converting to ProRes 422 at about 3x the file size.

There absolutely no reason to deviate from native when working with DVCPRO 50, unless your delivery requirements absolutely insisted on 720 x 486 output (and even then I'd consider blowing up the DVCPRO 50 master 1.25% at a post house - no-one will ever know.) There is little advantage converting to ProRes 422 at about 3x the file size.

Verdict: Native all the way.

DV/DVCAM/DVCPRO

These DV 25 formats would normally be edited natively, just like you probably have been for years. What we have now is another alternative for when DV source needs to be composited or color corrected extensively (like through Color). When extensive color correction or compositing is required the additional color space and lower compression gained by using ProRes 422 might make sense.Although we move from 4:1:1 colorspace to 4:2:2 you don't create any more information just because you convert to ProRes 422! Going ProRes 422 stems the losses, so to speak, and gives more calculating room for the compositing or color correction.

These DV 25 formats would normally be edited natively, just like you probably have been for years. What we have now is another alternative for when DV source needs to be composited or color corrected extensively (like through Color). When extensive color correction or compositing is required the additional color space and lower compression gained by using ProRes 422 might make sense.Although we move from 4:1:1 colorspace to 4:2:2 you don't create any more information just because you convert to ProRes 422! Going ProRes 422 stems the losses, so to speak, and gives more calculating room for the compositing or color correction.

![]() If you do convert, the perfect path would be to play out via SDI and capture that directly to ProRes 422, as above, as most professional decks with SDI output from this format do color smoothing to recreate the missing color information on the SDI output. This is a big benefit when compositing or color correcting. We can fake this by adding a 4:1:1 Color Smoothing filter to the clips before batch exporting to ProRes 422 in Standard Definition.

If you do convert, the perfect path would be to play out via SDI and capture that directly to ProRes 422, as above, as most professional decks with SDI output from this format do color smoothing to recreate the missing color information on the SDI output. This is a big benefit when compositing or color correcting. We can fake this by adding a 4:1:1 Color Smoothing filter to the clips before batch exporting to ProRes 422 in Standard Definition.

Verdict: Native most of the time, otherwise either capture via SDI directly to ProRes 422 or Batch Convert to ProRes 422 after capture with the 4:1:1 Color Smoothing Filter applied. (Folks in PAL markets you're really going to have to spring for the deck rental as there's no equivalent Color Smoothing filter for 4:2:0. In PAL only DVCPRO support 4:1:1.)

Mixed Source

When your source is coming from all over the place, then settle on a Timeline format that will work well with all sources. Ultimately everything is placed in a Timeline, even with Final Cut Pro's new open format Timeline. The logical choice for this is ProRes 422 (SD or HD depending on your primary deliverable) at the frame rate of your primary footage: 23.98 (24) or 29.97 (30), unless your delivery requirements require uncompressed editing.

So, in conclusion, you want to either: stay native or use ProRes 422 unless you're required to do the final edit in uncompressed. There is so little difference between uncompressed and ProRes 422 that, when output via SDI to a master tape, there will be no way to tell that the edit was not done in uncompressed, but I know you'd be honorable and use 5 times the amount of much more expensive storage just to stick by the letter of the agreement. WouldnÕt you?

*ProRes 422 requires a Quad G5 or Xeon-based Intel Macintosh for real time capture. On other systems you can capture to uncompressed and encode to ProRes 422 before editing in a batch export from Final Cut Pro.

Converting to ProRes 422 using Batch Export.

Now, you have a choice as to whether you export via Batch Export, or Media Manager. Both will do the conversion and both methods retain Timecode, so whether you use one or the other depends entirely on which you like better. Since Apple has a movie available on how to export to ProRes 422 using Media Manager, I'll focus on the Batch Export method.

Now, you have a choice as to whether you export via Batch Export, or Media Manager. Both will do the conversion and both methods retain Timecode, so whether you use one or the other depends entirely on which you like better. Since Apple has a movie available on how to export to ProRes 422 using Media Manager, I'll focus on the Batch Export method.

Using Media Manager has the advantages of creating a new project containing the converted material (so you'd have a capture project and a ProRes 422 project) and Media Manager tells us ahead of time how much space we'll need. (Expect it to be more than native capture for all FireWire-based formats.)

Batch Export has the advantage of being able to select multiple Bins and export as one batch (say overnight) and doesn't have the complexity of multiple projects. (Import the ProRes 422 footage into the original project.)

- With the clips selected in the Bin or Browser, Right+click or Control+Click to bring up the Context menu and select Batch Export. The Batch Export window opens.

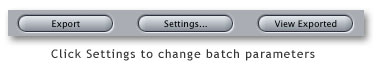

- In the Batch Export window click the Settings button at the middle of the bottom of the window. The Settings dialog will open.

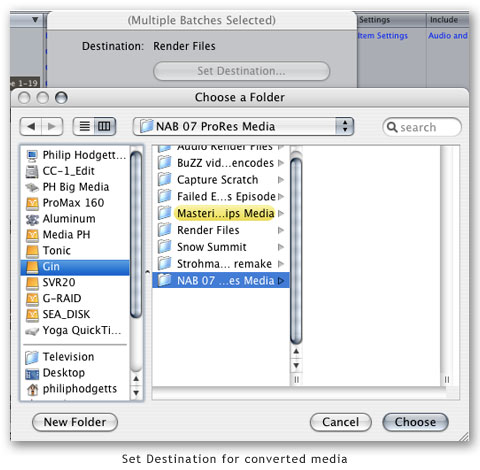

- Set a suitable location for your converted media files in the Destination. This should be a media drive or RAID.

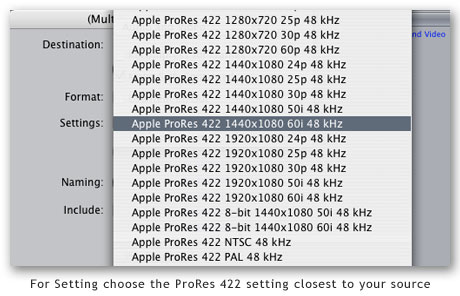

- Set the Format to QuickTime Movie (the default)

- From the Settings pop-up menu choose the nearest match to your source material.

- For XDCAM HD, HDV and HDCAM you could use a 1:1 pixel match and choose 1440 x 1080 for 1080 60i or you can choose full raster 1920 x 1080. Since Final Cut Pro knows what to do with 1440 x 1080, and you can't create information that's not there you might as well work with native, non-square pixels at 1440 x 1080.

- Coming from HDCAM, HDCAM SR or even SDCAM, I'd mostly choose ProRes 422 (HQ). For HDV there's little advantage to choosing the higher quality (HQ) version of the codec.

- For 720P source, there is only a full raster option in ProRes.

Batch Conversion of captured clips retains Timecode information in case you ever need to recapture. Any filters you add will be processed during export as will any speed changes.

Philip Hodgetts is a digital media visionary, co-developer of the

popular Intelligent Assistants range of training for Final Cut Pro

and Boris Products, creator of the Digital Production BuZZ and co-

founder of Open Television Network. He is also a consultant on post

production workflows through the http://bigbrainsforrent.com consultancy.

He can be contacted at philip@intelligentassistance.com.